Tatsuzo Shimaoka

Japanese, 1919-2007

There were quite a number of exceptionally gifted studio potters in the last century but perhaps only a few dozen that could truly be called great. Tatsuzo Shimaoka was one of these. He was, arguably, the finest Japanese potter of his generation and, because of his remarkable “rope-impressed” style, was one of the very few potters to be designated a “Living National Treasure”. He has been exhibited worldwide and became one of the 20th century's most influential ceramic artists.

Tatsuzo Shimaoka was born in 1919 in Tokyo into a family of master braid makers. He became inspired by ceramics on a visit to the Japan Folk Art Museum in 1938 — he was deeply impressed by the beautifully simple pots and the Mingei (folk craft) philosophy behind them. It was a turning point in his life: “When I was lost at what to do in the future, (this) was like fertile rain on barren soil.” He applied to the Tokyo Institute of Technology despite the objections of his father, Yonekichi (who was a third-generation braid master). As the eldest son, he was expected to follow in his father's footsteps — not to pursue a career as a potter.

Shimaoka graduated in 1941 with a degree in industrial ceramics and joined the army. He spent a period as a prisoner of war. The war also shaped his career; the family business was undermined when the demand from the occupying American forces caused the price of silk to skyrocket. Instead, he moved with his family to Mashiko, a centre of traditional ceramics, where in 1946 he became a pupil of the celebrated potter Shoji Hamada — initially as an apprentice for three years. Hamada, a co-founder of the Japan Folk Art Museum, had been working at Mashiko since the 1920s and is almost universally considered to be one of the finest potters of the last century.

After working for three years at the Tochigi Prefecture Ceramic Research Centre, Shimaoka returned to Mashiko and established workshops adjacent to Hamada's, building his own five-chambered, wood-fired, climbing kiln. Having at first tried to master a wide range of styles, he was finally coaxed by Hamada to find the technique that interested him most and stick to it. He hit upon the use of impressed rope design and this became a source of unending interest to him for the next 50 years. It is perhaps ironic that it was his father's braided silk cords that he used to create the decoration on his pots.

Related Links

* Lives Remembered: Tatsuzo Shimaoka

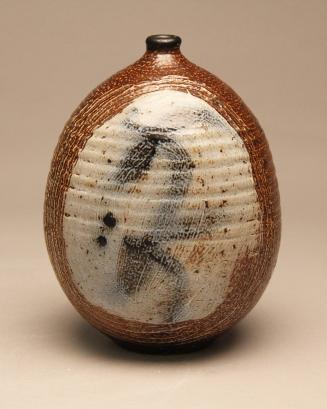

Shimaoka's rope-inlay technique is essentially the fusing of two ancient craft forms. Prehistoric Japanese Jomon earthenware often used a distinctive rope decoration and this form of slip inlay was typical of Korean Yi Dynasty “punch'ong” wares much loved by early Japanese tea masters. To create patterns Shimaoka would roll a braid or a wooden dowel wrapped with cord over the still-pliable surface of a vessel and then apply a white clay slip to fill the impressions. After wiping away the excess slip, he would apply a transparent glaze overall. In Shimaoka's hands this became something quite new and, seemingly, of almost infinitely variety. Sometimes it was used quite heavily without decoration to emphasise the form of a pot — with very different effects depending on whether the rope marks cross diagonally or straight, whether they follow the contours of the pot or work in opposition. At other times, the impressions were more delicate and acted as a radiant background for splashed and dripped glazes, brushwork or rondels, and sometimes even overglaze enamels. He also made exceptional use of the combination of a blue salt glaze over the cord patterns. His pots combine a rich and vibrant decorative quality with a great sense of tranquillity.

His reputation grew fairly rapidly. In 1962 he received from the Japan Folk Art Museum his first (of many) prizes and began to establish a series of annual exhibitions at the Matsuya Ginza department store in Tokyo, the Hankyu department store in Osaka, the Japan Ceramic Art Exhibition and the Chunichi International Ceramic Exhibition. He began exhibiting abroad in 1964 with a three-month teaching tour of North America and had a great many foreign exhibitions since. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s he undertook teaching tours of Australia, New Zealand and, especially, Canada.

Shimaoka was a dedicated follower of Hamada and most of his working methods and materials were essentially the same — thrown or press-moulded stoneware and glazes generally derived from local materials. He also shared Hamada's gentle nature and genuine humility. However, though Shimaoka's forms and glazes were clearly inspired by his master, there is no mistaking his pots for those of Hamada.

He considered his pottery and his making process to be part of the Mingei revival popularised by Soetsu Yanagi near the beginning of the last century. He is widely considered to be the natural Mingei successor to Hamada but, strictly speaking, this is not the case. The term is meant to apply to anonymous craftsmen who, without artistic aim, created functional objects of great beauty. Shimoaka was much too much of a ceramic artist to completely fit this description — right to the end of his working life he continued to expand his repertoire and explore new creative possibilities. Even in his eighties he made few concessions to age. Back pain meant switching from a kick-wheel to an electric one, but each new exhibition brought surprises.

He did, however, continue the tradition of potter and apprentice that had so impressed him when he had studied with Hamada. Fukuyan Kamiya came from Hamada in the 1950s and became the pottery foreman. Dozens of apprentices learnt their skills with Shimoaka, including Ken Matszuaki, Masayuki Miyajima and Noriyasu Tsuchiya, who all became well known for their own work. Through his exhibitions and his teachings he became a great source of inspiration to potters all over the world.

In 1996 he was designated “Important Intangible Cultural Property” — more commonly known as “Living National Treasure”. Japan is a country where ceramics is more highly revered than either painting or sculpture and this is the highest honour that can be given to a craftsman. Very few potters have ever received it and probably none has been more deserving. He was also awarded the esteemed Order of the Rising Sun in 1999. Typically, these great honours barely changed Shimaoka's nature.

Tatsuzo Shimaoka, potter, was born on October 27, 1919. He died on December 11, 2007, aged 88

Person TypeArtist

Terms